Opera wears many hats to tell the world of tales and fantasies. The brim, at times, shades the truth from the band, which is focused on order. All while the crown-shape peaks at the climax to eventually unveil the crown. Its versatility reveals convincing faces of truths and lies whose objective is to gain a faithful believer. Once you’re in opera, it’s hard to escape its aura.

The opportunity to convey a wide array of emotions through a story's unfolding gives opera its magic. As per the natural process, means of expression progress with time, and this is demonstrated in the different eras within opera.

Late Renaissance (14th - 17th Century)

The Renaissance followed the Middle Ages and is believed to have started in Italy and eventually spread to western and northern Europe. The Renaissance saw a rise in people of influence in literacy, science, art, and philosophy. Leaders in these fields included William Shakespeare, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Galileo, to name a few. Notable opera composers during the Renaissance were Claudio Monteverdi, Jacopo Peri, and Giulio Caccini. Art, architecture, and science blended and revolutionized the human experience. According to some historians, the advancement of knowledge came to the forefront during the Renaissance due to a lack of progress in the Middle Ages.

Let’s go back to the early 17th century in Mantua, Italy, during the transition from the Renaissance to Baroque. Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi pioneered opera with the success of L’Orfeo. Monteverdi’s style was influenced by his teacher Marcantonio Ingegneri, an expert madrigalist, and Flemish composer Giaches de Wert who wrote avant-garde music. The styles of his teachers propelled Monteverdi’s imaginative mind, which was filled with mythological stories and musical tension. Drama was at the center of this art form, expressed through song and recitative.

Written in 1607, Monteverdi collaborated with librettist Alessandro Striggio to tell the story of Orpheus’ descent to Hades in an attempt to bring his wife Euridice back to the living world. Though L’Orfeo is not the first surviving opera (Dafne was composed by Jacopo Peri in 1597), its early arrival offers exciting information on the sounds of early opera.

The opera heavily focuses on Greek mythology and two opposing worlds, Hades and the fields of Thrace. The primary goal of this operatic form was to use differentiating musical elements in an effort to tell a cohesive story through drama. Monteverdi combined an array of musical characteristics to create the form of opera in L’Orfeo. The aria, recitative, dances, strophic song, choruses, and musical interludes (ritornello, which translates to “little return” in Italian) dramatized the plot and propelled the storyline. The instrumentalists were involved in the music-making process and were often required to improvise during live performances. According to Harnoncourt, the conductor of L’Orfeo, the instrumentalists were composers and were expected to incorporate their creativity in each performance rather than performing strictly what was on the score. This was true for the singers as there were specific moments written in the score for them to include their own embellishments. Music example: Montserrat Figueras sings "Dal mi permesso" from Act 1 Prologue in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo

Baroque (17th - mid 18th Century)

The Baroque period lasted from roughly 1600-1750 and arguably influenced the following two periods greatly. Baroque derives from the Portuguese word barocco, which translates to ‘irregular pearl.’

The 1600s in Europe unveiled religious wars and absolutism. The Thirty Years' War and the English Civil War combined dominated for fifty years and revealed rigid dichotomies in opinions on religion and politics. The Age of Absolutism saw a shift in the emphasis from religion, to power and status. Total shifts in power can be seen from Louis XIV of France and Peter the Great of Russia. Their goals to build a powerful infrastructure by dominating countries with desirable resources and influence on trade were executed by extreme measures. However extreme, adopting radicalized ideologies for the purpose of war, introduced people to new places, cultures, practices, and music.

The 1700s is widely known as the Age of Enlightenment and was considerably influenced by the English Civil Wars. During this period, traditions were replaced with individualism and scientific and philosophical exploration. German philosopher, Immanuel Kent, summarizes the Age of Enlightenment in his essay What is Enlightenment?:

Enlightenment is man's emergence from his self-imposed nonage. Nonage is the inability to use one's own understanding without another's guidance. This nonage is self-imposed if its cause lies not in lack of understanding but in indecision and lack of courage to use one's own mind without another's guidance. Dare to know! (Sapere Aude!) "Have the courage to use your own understanding," is therefore the motto of the enlightenment.

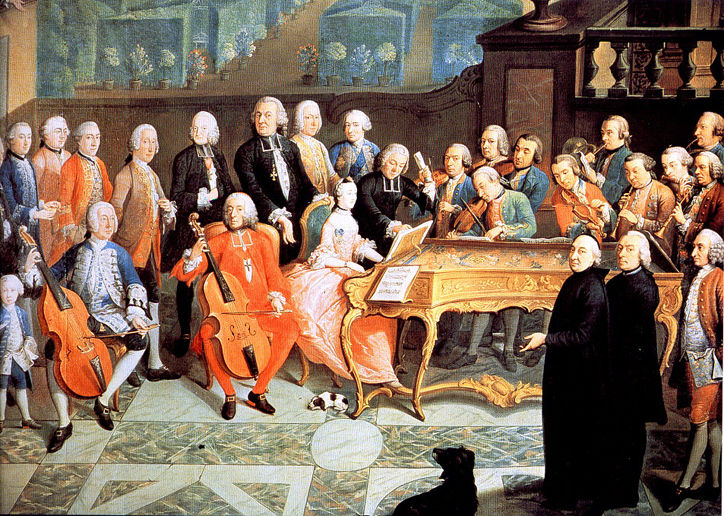

Breakthroughs in developed ideologies sparked an advancement in music. There was a rise in ensemble, and opera consisted of intricate harmonies with expanded storylines that emphasized various classes, hierarchies, and love. With this growth of music came exposure. Music was now integrated into outdoor spaces, political spaces, and various special occasions.

At the beginning of the baroque period, opera was available to the courts and those in the aristocracy. Because the general public did not receive the same exposure to opera music, it was seen as an art form reserved for those with money and status. However, the first public opera house opened in Venice, Italy, in 1637. Teatro San Cassiano would bridge the general public with opera and ensemble music.

Tamerlano premiered on October 31st, 1724, with a libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym and music by George Frideric Handel. It is a three-act opera set in 1402 in Prusa, Turkey (currently known as Bursa, Turkey). The story tells of the tumultuous relationship between the Ottoman emperor, Bajazet, and Tamerlano, emperor of the Tartars. Intense love triangles are accompanied by a theme of love’s ability to turn darkness into light. Take note of the music examples below and hear how ornamentation is a key characteristic in this period of music.

The orchestration is light compared to the orchestration in the following periods. The score of Tamerlano calls for two recorders, two flutes, two oboes, a bassoon, two horns, strings, and continuo instruments (cello, lute, harpsichord). Boundaries are explored in the music and libretto. Handel dedicated the main role to that of a mature tenor voice during a time when the castrati voice was in popular demand. The libretto had dark undertones featuring suicide, a topic many composers avoided.

Music Examples: Tamerlano’s aria A dispetto (alto/castrato)

Bajazet’s aria Forte e lieto a morte andrei (tenor)

Classical (Late 18th - Early 19th Century)

The Age of Enlightenment took over the Renaissance era from the late 17th century to the 18th century and paved the path for Romanticism. Also known as the Age of Reason, individuals yearned for the understanding of life through exploration by challenging traditions. Humanism was a widely accepted narrative where human interests and reason were at the forefront of intellect. With the invention of the printing press in the early 15 century, knowledge could influence broader audiences.

The Age of Enlightenment impacted storytelling and characters within opera. Opera during the Baroque showcased drama through heavy ornamentation in orchestration and melodies, while characters consisted of gods with storylines influenced by Greek mythology. The Age of Reason introduced a shift in music styles and characterization and is often observed as a defiance against Baroque traditions. Gods were replaced by humans, and elaborate vocal showcasing was diminished. Additionally, realism was at the center of libretti. Storylines incorporated realistic situations, thereby connecting to audiences through relatability. Let’s look into Act 1 of Le nozze di Figaro to see these influences.

Le nozze di Figaro, arguably one of the most famous operas of all time, premiered in 1786. Mozart wrote the music to The Marriage of Figaro at 30. Da Ponte, the librettist, based the text from the French play La Folle Journée, ou Le Mariage de Figaro (The Mad Day, or the Marriage of Figaro), written by Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais in 1778. The opera consists of four acts and tells the eventful stories of complex characters and their emotional love journies that take place on a single day.

Le nozze di Figaro Act I

The opera is set in Seville, Spain, at Count Almaviva’s palace. Figaro, the Count’s personal attendant, is the opera's protagonist and is set to marry Susanna, Countess Rosina Almaviva’s maid. Susanna expresses her concerns to Figaro about the Count’s advancements toward her. This is troublesome, considering the Count has the right to lie in bed with the servant girl before her husband on her wedding day.

Bartolo, a doctor, and Marcellina, Bartolo’s housekeeper, are upset with Figaro and Susanna. Bartolo is infuriated with Figaro for orchestrating the union of (Countess) Rosina and Count Almaviva. Marcellina is jealous Susanna is marrying Figaro, as she was promised to be his wife after Figaro was unable to pay a debt.

Cherubino, the Count’s messenger (also known as a page), attempts to understand his prevalent infatuation with women and asks Susanna for assistance in courting the Countess. However, he is supposed to be elsewhere as he was caught by the Count with Barbarina, the gardener’s daughter. Just as he was to receive advice from Susanna, the Count enters the room, and Cherubino hides behind a chair. The Count flirts with Susanna and is suddenly forced to conceal himself as someone else is heard approaching. He hides in the exact location as Cherubino, prompting Cherubino to hastily move on top of the chair while Susanna covers him with a dress. In comes Don Basilio, a music teacher, complaining of Cherubino’s attraction towards the Countess and Barbarina. Don Basilio explains that he found Cherubino with Barbarina under a kitchen table. He then expressively grabs the dress that is concealing Cherubino to demonstrate how he lifted the tablecloth, revealing none other than Cherubino. Irate, the Count reveals himself and declares Cherubino ready for army duty as punishment. The Count must also keep in mind Cherubino has heard his conversation with Susanna and can use this information to make advances toward the Countess. Cherubino is saved from further embarrassment when Figaro enters with a crowd of peasants from the Count’s estate. Figaro and the crowd begin singing of the Count’s abolishment of the droit du seigneur, the right to sleep with the servant girl before her husband on the wedding day. The Count postpones Figaro’s request and vows to help Marcellina marry Figaro.

It is evident that fundamental human interactions, traditions, and honest reactions are at the forefront of the plot in The Marriage of Figaro. In the first act, we discover men become territorial when other men approach their significant others, women tend to gossip and protect the immature, infidelity is frowned upon in the lower class but expected amongst males with power and status, and accountability can be skirted if you play your cards correctly. The many situations in Act I are relatable to the human experience, especially compared to unrealistic plots with gods and Greek mythology in the previous periods.

Music Example: Le nozze di Figaro Act 1 Cosa sento! (Cherubino is discovered hiding in a room with Susanna)

Sources:

https://www.npr.org/2010/01/08/122328598/the-root-of-all-opera-monteverdi-s-orfeo

https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/bitstream/handle/2346/72711/STEINER-PROJECTPAPER--DMA-2017.pdf?sequence=1

https://www.sfopera.com/learn/about-opera/a-timeline-of-opera-history/

https://www.musicnotes.com/now/news/musical-periods-the-history-of-classical-music/

https://www.operasense.com/facts-to-know-about-the-marriage-of-figaro/

https://www.sfopera.com/learn/about-opera/a-brief-history-of-opera/

https://galaxymusicnotes.com/pages/learn-the-story-behind-the-marriage-of-figaro-by-mozart

https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Marriage-of-Figaro-opera-by-Mozart

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-musicapp-medieval-modern/chapter/monteverdis-lorfeo/

https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=muscfest2019

https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2020/03/09/ornamenting-monteverdi/

Comments